Something I have to do early in The Arena — the book I’m writing — is explain rainfall patterns in the Middle East, because they drive conflict. But to do so without getting into too much detail, and probably without mentioning the key measure, the isohyet.

Just as a contour line shows altitude and an isobar shows atmospheric pressure, so an isohyet shows rainfall on a map.

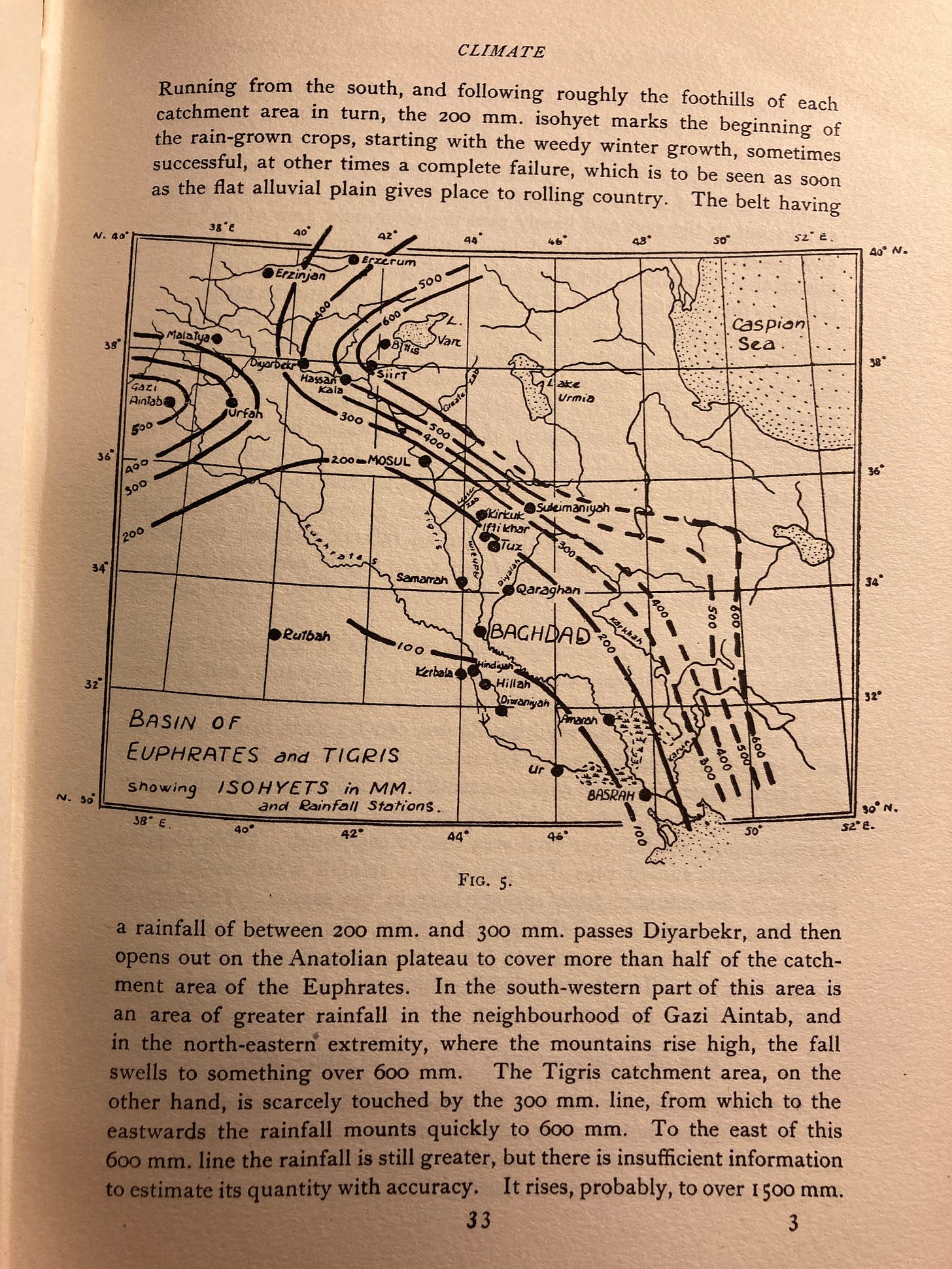

Here’s an example, from Michael Ionides’s useful book The Regime of the Rivers Euphrates and Tigris. Ionides was a water engineer in Iraq. He also worked for MI6 and wrote an excellent book on Iraq in the 1950s, Divide and Lose, but that’s a story for another day.

Here’s his isohyet map:

The isohyets mark the line receiving a certain amount of rainfall. So the area bounded by the 200mm line and the 300mm line indicates the area receiving between 20 and 30 centimetres of rain per year. Mosul and Kirkuk lie in this zone.

Generally speaking, the “Fertile Crescent” is seen as being the Goldilocks zone receiving between 250mm and 500mm of rain a year — enough to sustain rain-fed agriculture.

What is interesting here is that Ionides’s map shows how ancient Sumer (the area between the rivers, south of Baghdad, and location of the great ancient cities like Ur) didn’t get enough rainfall to sustain agriculture. Due to the manpower needed to maintain irrigation systems, agriculture didn’t originate in the south, but further north where there was rain. But these southern cities pioneered large scale irrigation using the rivers’ water, permitting agriculture in an area where it could not be sustained by rainfall.

Unlike contours (except if we are talking about geological periods of time), isohyets shift, just as isobars do on an old-fashioned weather map.

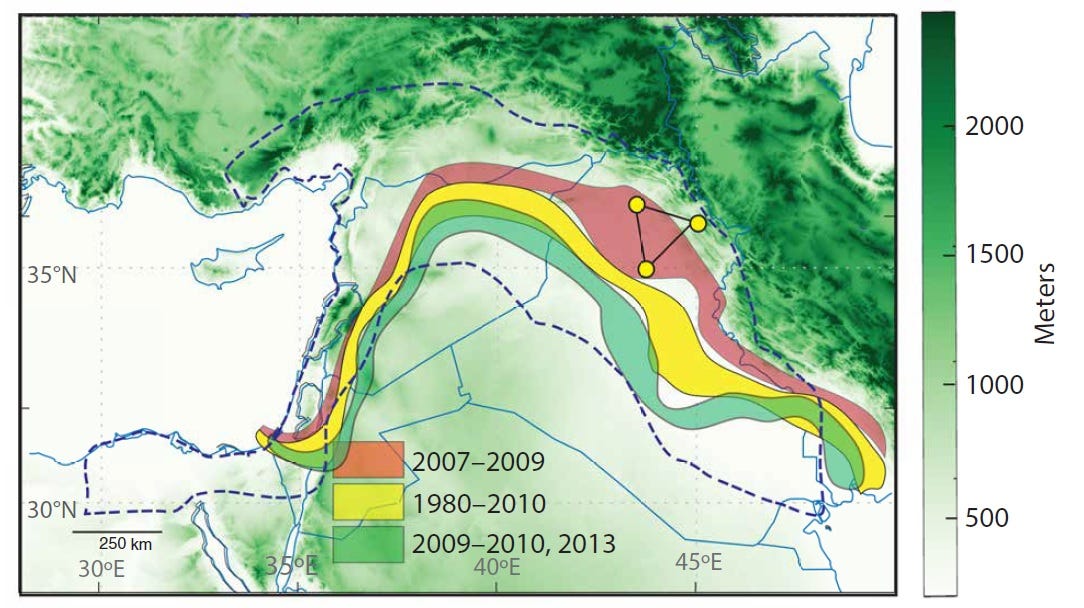

Here’s another really interesting map that shows how. In fact I’d say it’s one of the most interesting maps I’ve seen while working on this book. It’s from a 2019 article on the “Role of climate in the rise and fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire”, by Ashish Sinha and others. The triangle marked by yellow dots shows the Assyrian heartland, and the article argues that a drying climate played a significant role in the collapse of the Assyrian Empire in the late 600s BC. The yellow dot marking the northern apex of the triangle is Mosul/Nineveh.

Despite the article’s title this map shows rainfall in the 2006-13 period, when drought hit this part of the world: and it shows just how dynamic the “Fertile Crescent” actually is.

The article says that the “Shaded regions show the area bounded between the 200- and 300-mm isohyets for the dry (2007–2009), wet (2009–10, 2013), and mean climatology (1980–2010) periods.”

Red is the dry period, green the subsequent wet period that ended the drought, and yellow the average for the period since 1980.

Look how much this band can shift, especially in the eastern Fertile Crescent. In northern Iraq, the distance between the middle of the green band (wet weather that ended the 2006-09 drought) and the red band (the drought era) must be 250km.

It’s also interesting how the proximity of the Mediterranean and the microclimate it creates means that in the western Fertile Crescent the bands are narrower but also move about less. And look at that niche in NW Syria which receives more than 300mm of rain each year. This was colonised by the Seleukids after Alexander the Great, and then formed the bridgehead for Rome in this region.

That map shows recent rainfall. But what it really reveals is just how volatile the climate in parts of this region is — there are big differences in rain from season to season and from year to year

Imagine you were a farmer who traditionally farmed in the yellow area, where in recent times there has generally been enough rain to support your crops. During the drought your crop failed repeatedly due to lack of water and you were forced to borrow money to survive.

Now imagine you were a herder: you need less than 200mm of rain a year, but you still need some rain. Normally you live on the margins, between the agricultural zone and the desert, roaming from place to place to find grazing for your sheep and goats and possibly tolerated by the farmers at two times of year — after the crop germinates and after harvest. In that red era, you would be looking for grazing in the yellow farmland zone.

And that chase - for grazing in farmland during periods of drought - has been one trigger of conflict over the millennia.